Yo dudes, I was just reading

this cool blog over here, and I thought of our hosts.

There’s a story I like, about this little kid who wants to be a writer. So she writes a story and shows it to her teacher.

“You misspelt the word ‘ocean’”, says the teacher.

“No I didn’t!”, says the kid.

The teacher looks a bit apologetic, but persists: “‘Ocean’ is spelt with a ‘c’ rather than an ‘sh’; this makes sense, because the ‘e’ after the ‘c’ changes its sound…”

“No I didn’t!” interrupts the kid.

“Look,” says the teacher, “I get it that it hurts to notice mistakes. But that which can be destroyed by the truth should be! You did, in fact, misspell the word ‘ocean’.”

“I did not!” says the kid, whereupon she bursts into tears, and runs away and hides in the closet, repeating again and again: “I did not misspell the word! I can too be a writer!”.

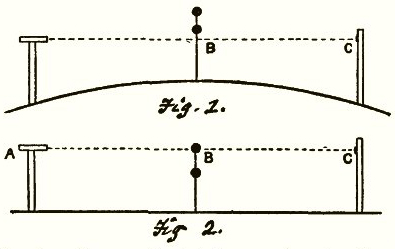

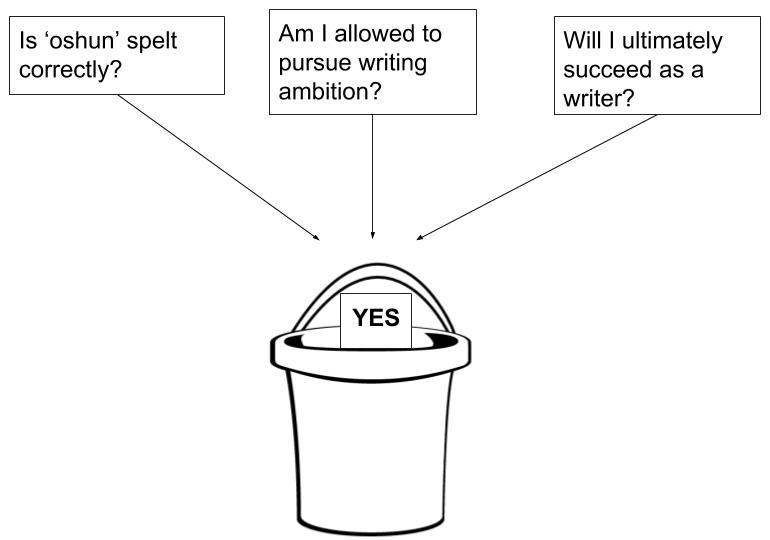

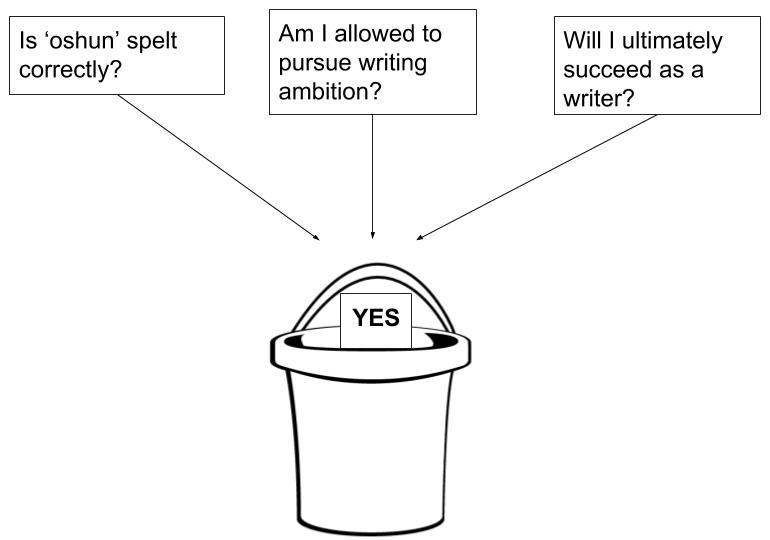

I like to imagine the inside of the kid’s head as containing a single bucket that houses three different variables that are initially all stuck together:

...

To briefly give several more examples, without diagrams (you might see if you can visualize how a buckets diagram might go in these):

- Carol is afraid to notice a potential flaw in her startup, lest she lose the ability to try full force on it.

- Don finds himself reluctant to question his belief in God, lest he be forced to conclude that there's no point to morality.

- As a child, I was afraid to allow myself to actually consider giving some of my allowance to poor people, even though part of me wanted to do so. My fear I was that if I allowed the "maybe you should give away your money, because maybe everyone matters evenly and you should be consequentialist" theory to fully boot up in my head, I would end up having to give away *all* my money, which seemed bad.

- Eleanore believes there is no important existential risk, and is reluctant to think through whether that might not be true, in case it ends up hijacking her whole life.

- Fred does not want to notice how much smarter he is than most of his classmates, lest he stop respecting them and treating them well.

- Gina has mixed feelings about pursuing money -- she mostly avoids it -- because she wants to remain a "caring person", and she has a feeling that becoming strategic about money would somehow involve giving up on that.

It seems to me that in each of these cases, the person has an arguably worthwhile goal that they might somehow lose track of (or might accidentally lose the ability to act on) if they think some *other* matter through -- arguably because of a deficiency of mental "buckets".

One example related to flat Earth belief:

- The Earth is flat

- My science teachers couldn't explain how gravity works

If these both point to one bucket, flipped to Yes, it becomes impossible to change item 1 by itself if this person's teacher really did say some boneheaded things about gravity. If there is a longer list of points that includes, say, Rowbotham's ideas on perspective, electromagnetic acceleration, and the space travel conspiracy, and these are all in one bucket, there can be no adjustment of any of the related points.

This can be seen in the topic overlaps in many of the ongoing threads on this site: Proving A' would mean B, but it must be !B because !C, and I know !C because !D. Heated arguments ensue about each topic. Meanwhile, the thread's original topic A is left unaddressed.

With the buckets model in mind:

Is it possible to isolate the sub-topics involved in arguing the shape of the Earth?

Is there a most important topic that could settle the question, if sufficiently answered?

Does flat Earth belief correlate with bucket shortage?